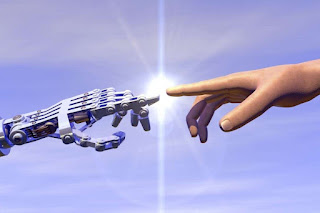

' The Psychology of the Tangibles. ' We are posed hesitantly before a future in which artificial intelligence [AI] and digital technology will be an integral part of our lives.

From decision-making to production capabilities, education platforms, medical practice, warfare business transactions, governance, policing and many more functions we cannot even anticipate.

Hesitant, because as Geoffrey Hinton, ' the godfather of AI ', warns, within the next five years, AI could dominate our lives with more intelligence than humans. More alarmingly, it can potentially make decisions independently of human instructions.

He has worked on deep learning and AI since the 70s, so his words carry weight.

Digital technology is already part of our lives - on our phones, laptops and in our surroundings. We can walk through a Van Gogh painting or among the dinosaurs in a museum and travel to distant places with virtual reality devices.

Virtual assistants, the ever-attentive Siri and Alexa in our homes, respond to our most trivial needs.

It's all very exciting. No more maps when trying to find the best route, no space-consuming shelves full of books, and no need to depend on others for information.

While digitising - converting data to a digital form - is so essential to preserving books and images, digitalising or using digitised data to create systems is a grey area.

Experiencing the world with our five senses is integral to being human, to feeling alive. We make sense of our experiences when the brain combines information from sensory systems.

Sight, hearing and touch have been digitalised and it is claimed that smell and taste will soon be digitally available. It is difficult to not be sceptical of the ability of digital technology to truly replace multisensory experience.

While it may as a marketing tool, it cannot capture the real experience of jostling through a bazar hot and tired, catching snippets of conversations, and the weight of shopping bags cutting into the palms.

The poet William Wordsworth would not have compared Lucy to '' a violet by a mossy stone half hidden from the eye '' if his walks in the woods were virtual.

Some experiences are personal and unique - such as touching the rough stone of an old building, and seeing a thumbprint on a 4,000 year old terracotta toy from Harappa, feeling a sudden breeze rustling through a tree, or the smell of rain on parched earth.

As artificial intelligence and online interactions increasingly define our relationship with the world and other people, we must be careful not to lose touch with the very things that makes us human.

The Publishing of this Master Essay continues into the future. The World Students Society thanks Durriya Kazi.

.png)

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Grace A Comment!